Eddie (Ted)

An Airman in Canada, 1940-1946

During the Battle of Britain I received new orders. As I tore them open, my eyes grew wide in disbelief, ‘Canada!’

The war had caused such havoc in England that the Air Force couldn't adequately train new airmen. In Canada there was plenty of room and no danger. Crews, airplanes, ground personnel and back-up equipment were being sent there.

‘Canada!’ It still sounded like a dream come true to me as I waited to board the train which was to take me and the other troops to a port in Scotland. I was about to fulfill a childhood dream of crossing the seas, when I least expected it. My only sorrow was to leave family behind in a country where death was a daily threat.

We arrived at the port-of-departure and were marched up a gangplank into a huge troop ship. The vessel quickly filled with thousands of men divided into groups of two hundred. Our group was sent below decks where we were accommodated in numbered hammocks. They hung like dark clouds across a room. Each of us looked earnestly for the hammock where we were to store our equipment and sleep. “I hope we sail soon,” I said to the man who claimed the aerial bed next to mine.

“I hope we have a smooth trip. I get seasick,” he warned me. I noticed that he looked a little green.

The well-laden boat stopped in Northern Ireland. Then it turned and went back to Scotland, where we stayed in port another week. Apparently the U-boat activity made it unsafe for a single vessel to cross the Atlantic. A fifty-ship convoy gathered to accompany us, including a couple of destroyers and a battle cruiser.

On the upper deck of our ship, separated only by a rope, were several hundred German Prisoners. They were primarily pilots who had been shot down over England. Often they stood by the rope and signaled to us to trade with them. Some of the Germans spoke better English than we did, so we understood that they wanted cigarettes.

Every British soldier or airman, whether he wanted it or not, was allocated tobacco. I only smoked a little so had a lot to trade. We exchanged for bits and pieces of their uniforms: medals, badges, insignia and gloves.

Sometimes they stood and sang. The cadence of their music was militaristic and stirred us with its beauty.

Not to be outdone, we responded with:

Roll Out The Barrel,

British Soldiers, 1939

and

Pack Up Your Troubles,

D-Day Darlings

jolly tunes that had no military significance. They laughed at one of our songs,

We’re Going to Hang Out the Washing on the Siegfried Line!,

Sidney Lipton, 1939

They were convinced they would win the war. I’m glad that choral ability was not the criterion for winning the war, or they might have!

Aside from cigarettes, the German prisoners, because they were officers, were treated better than we British troops were.

“Ware, I was sent on a job to the Officer’s Mess this morning and saw menus, fine china, bread rolls, real meat, wine and desserts,” the man in the hammock next to mine complained one evening. I was amazed that he had noticed since he had been seasick since the day we sailed.

The swill that we soldiers were fed made us furious. In the morning we were given gray porridge. At noon a brown, gooey-gook they called stew. At night yellow curry with little bits of meat afloat in it. Day after day the same fare. We felt that we were being treated as pigs, the only difference being that the slop came on a plate.

At each of our meals the officer on duty was required to ask, “Any complaints?”

That night I stood up and responded, “Yes!”

As Oliver in Dickens’ great novel I raised my plate and asked, “How'd you like to eat this?”

“What's the matter with it?” The officer seemed a little worried.

“Well, taste it.” I dared him. “And while you are at it, try this coffee. The cook must have used yesterday’s dishwater to make it!”

He took my cup, gritted his teeth and siphoned a drop into his mouth, “Hmmmmm, not so bad!” then quickly returned it to me.

Each day the injustice and inequality was brought to the attention of the officer on duty. Sometimes the officer nibbled a little bit of our food to pacify us. On one occasion, to emphasize the point, a soldier brought a little human excrement into the dining hall with him, and mixed it with the brown stew on his plate. When the time came to register complaints, he then stood up and asked, “What does this stuff smell like?”

The officer went over and smelled the stew, “Ughhh,” he shouted, and spit. For a few days our rations improved, but then reverted back to the same as before.

Despite our miserable food, we enjoyed the balmy and beautiful weather in the South Atlantic. We reached there within a week. At that point, since we had passed the treacherous part of our voyage, our ship parted company with the convoy. We headed north alone.

After a few days of smooth waters the weather changed drastically. A hurricane was in our path. Our boat tossed in the waves like a child’s toy in the bathtub. I clung to the edges of my hammock and wondered how the ship was able to hold itself together as it shuddered and shook through the onslaught. Men were seasick all around me. Somehow the genes of my ancestors came through, and I was not ill. I thought of my grandfather Suckling and how he had relished his tussles with the sea.

As men groaned and retched around me I decided I had to get a breath of fresh air. I staggered to the stairs and climbed up to the hatch. We always wore our uniform, and I had on my parade cap. I found it stayed on my head better than my airman’s cap. On the deck I clung to the frame of the hatch and watched in awe as the ship’s bow submerged forty feet. With fearsome power it lurched up and washed the deck with huge waves. The propeller at the stern of the ship took its turn and lifted above the water, crashing back down into the waves.

Suddenly a gust of wind grabbed my hat. Instinctively I reached out for it and let go of the doorway. My body sailed like a rag after the hat and slammed against a rope that was stretched along the edge of the boat. I clung to it and, hand over hand, made my way to the stairway. I did not go for any more fresh breaths of air.

Almost a month after we had left Great Britain, in the winter of 1940, we arrived at the dock in Halifax, Canada, glad to be airmen!

We traveled by train across vast expanses of Canadian grandeur. Beautiful, but cold. The cold cut through us like a knife. The citizens of Winnipeg, alerted that British soldiers were to arrive at the train depot at a certain time, came by the hundreds to get their first glimpse of soldiers from the front lines. Our officers gave us two hours to fraternize with them.

A pretty young girl came up to me and introduced herself. “My name is Nancy. How was your trip?” she asked.

“Long!” I admitted, then changed the subject. “Your weather is cold here but your welcome sure is warm! Thank you for coming out to see us.”

“My mother said that I could invite someone home to a meal. Here is our address for when you have time off.” She extended a little hand-printed card to me.

Just then another girl came up to me. I quickly stuffed the card into my pocket, and shortly there was another address to join it. The two hours flew by and we were ordered onto trucks.

The Canadian barracks were long, low buildings that accommodated sixty men. A big, pot-bellied stove kept us from the unbelievably penetrating cold. The temperature often dropped below zero. Also, snow drifted and piled against the buildings, hangars, and across the airfield. Sometimes we awoke in the morning to six feet of snow heaped against the door.

Every two weeks we were given two days off. To get away from the barracks I called Nancy, the first girl that had come up to me at the train depot, and was invited to a meal at her home. The hospitality and food were wonderful. I was introduced to foods I'd never seen before: roast turkey, corn on the cob, and scrumptious strawberry shortcake with ice cream. After the meal I was taken to another new experience, a hockey game. I marveled at the speed and dexterity of the men as they skimmed across the ice on skates, slashing with their sticks at the puck in front of them.

Our new life in Canada was relaxed compared to bomb alerts and air raids in England. I started a jazz band that consisted of an accordion, a saxophone, my trumpet and drums. We played for dances and other social occasions. When men were sent home to England we went to the station and played a farewell to them. When new troops arrived, we met them in the same hospitable fashion.

On one trip to a social evening an acquaintance asked me. “Ware, what’s your first name?”

“Edward.”

“Is that what your family calls you?”

“No, they use Eddie, but I don’t like it. Sounds a bit feminine to me.”

“I know what you mean. My name is Robert. I don’t mind being called Bob, but Bobby reminds me of socks!” We both laughed. Then he asked, “What about ‘Ted’, that’s a nickname for Edward.”

“Yes! That’s better than Eddie, and less formal than Edward. I’ll use it!”

“By the way, Ted, do you have a steady girl back home?”

“No I don’t. Why?”

“Oh I just noticed that you don’t write much, and you don’t get a lot of mail.” Just then the train stopped for us to get off.

Time went fast in Canada, especially through the summer and gorgeous colors of fall. During the second winter I contracted pneumonia and was sent to the hospital for a few weeks. The Daughters of the British Empire came to the hospital, gave us cookies and invited us to their homes.

One family that befriended me was the Shuefelts. They were ten years older than I, with a baby daughter named Beverly. I spent many hours in their delightful company. At the end of a year I received extended leave of about ten days and took a trip with the Shuefelts to America where I saw Yellowstone Park.

The following year, I took a train trip to New York City with another friend. We wore our uniform and visited servicemen's clubs. Americans went out of their way to entertain us. We were taken to a Broadway show and watched women swoon over Frank Sinatra. I had never seen anything like it! We sat in the back of the large auditorium and watched as various entertainers came on stage. The crowd was rude and unruly and booed everyone but Sinatra. One entertainer played a banjo. Someone threw a coin on the stage at him, which is the height of entertainment insults. The player stopped his performance, looked down at the audience with absolute disdain, and said, “Who threw that coin?” The hall became quiet. He finished his act.

Sinatra came on next and the crowd started to coo and scream. Some women fainted while he sang. My friend turned to me, “Can you believe it?”

“No, I can’t understand it!”

We visited bars and clubs where jazz music was played. We met Louis Armstrong, Lionel Hampton, Gene Krupa, and Bud Freeman. Of course we went to see New York City’s famous lady, the Statue of Liberty.

On our way back to Canada we stopped at Niagara Falls. We were awed by the powerful falls and their rugged beauty. Afterward, we returned to the depot to board the next train to Canada. It was full, so we split up looking for empty seats. My buddy took the first one he could find. I looked around and saw a seat beside a young woman. As I sat down beside her she shouted, “Look at this man! Pig! He’s trying to get fresh with me!”

Baffled, I looked around to see whom she referred to, and realized that she meant me! “No Madam! This is the only seat available! I have no such intentions!”

“All men are alike. I hate you all. You’re all pigs!” She said loudly.

“I’m sorry to hear you say that. You probably have had reason to think so.” I was furtively looking for somewhere to escape.

“My husband was killed in France. Why should he have been sent over there anyway? I hate him for going and leaving me.”

It was the first time I viewed the war from the perspective of a woman. I was relieved that I did not have a wife to hate me for a choice that was made for me. She continued to berate all males. Before another seat became available she had run out of verbal ammunition and started to get friendly, even brazen. I was delighted when she got out at the next train station.

As I thought of my home in England, I sometimes felt guilty that my life in Canada was so good and my loved ones were suffering privations. My mother wrote to me every week. Two or three times, I received letters from my father. I had a couple of girlfriends whom I went to dances with, but I wasn't really interested in them. One by one my buddies, most of them younger than I, married Canadian girls.

I decided it was time for me to make some important decisions regarding my future. On a beautiful fall afternoon I went for a walk and sat down on the grass, leaned up against a tall pine tree and I began to think of all of the girls I knew. Whom would I want to spend the rest of my life with? There was Nancy, a nice Canadian girl… If I married her I could stay in Canada. For some reason the thought did not keep my attention. Then there was Lily, a pretty girl with rich parents who had been quite friendly. My heart did not stir at that suggestion either.

I thought of British girls, Jean from Bow, and Nelly the friendly nurse. Fun memories, but that was all. I lay back on the green earth and looked up at the blue sky. My heart beat faster. What was it about that beautiful blue? I closed my eyes and saw the same blue in a certain little country lassie’s eyes. Milly Halliday, of course! I sat bolt upright, my thoughts fully alert. Where could she be? Maybe she was married, or had died in a bomb, or wanted nothing to do with me! After all, I hadn’t seen her in ten years. I no longer was content to stay in Canada. I became restless and counted the days ‘till I would be sent back to England. Maybe, just maybe, Milly wasn’t married…

I was repatriated to England in February of 1944. I decided to go to see Mrs. Halliday, Milly’s mother, as soon as possible. I must find out where Milly was. After the ship docked, I was transported to my new assignment, an airfield 70 miles from London. I then bought a motorcycle and traveled home to my family and hopefully, to Milly.

The pall of smoke from burnt buildings was visible miles before I reached London’s outskirts. The streets were clogged with rubble. I had to get off of my cycle and push it. I passed weary, stumbling firemen, almost asleep on their feet, methodically hosing out the fires. Bandaged, dazed homeowners shuffled along as they sifted through their home’s charred remains. A lump rose in my throat that nearly choked me; what if my street was in tatters?

To my great relief I found my parents’ home and neighborhood undamaged. They were delighted to see me and kept me busy recounting my experiences. My brother Cliff had grown taller than I, yet was still the jovial young man I remembered. My sister was more beautiful than ever. She had many American suitors, but was most interested in a British sailor, Ron Giles.

Finally, I mustered the courage and found the opportunity to visit the Halliday home. I was facing my worst fear: Milly would be married. Timidly I knocked at the front entrance. Mrs. Halliday opened the door. “Edward Ware! I am so glad to see you! Oh, this is wonderful! Do come in.” She made me feel so welcome. “Come in and have a cup of tea!”

After I sat down, I asked her about the war and how it had affected her family. As politely and diplomatically as I knew, I went through names of the family. “How is your husband, and John? And how about Ruth and Gladys, Elsie and Grace?” And casually I asked, “Now, Milly. She's married, of course?”

“No! No!” Mrs. Halliday said.

“Oh! Oh! Well, that's nice.” My heart was pounding.

“She’s due home any minute.”

Just then the front door opened and a sweet voice called, “Hello Mummy! I’m home!”

When Milly entered the dining room I knew I could not live without her. She was the same sweet-faced, blue-eyed English country girl that I had remembered.

After her initial look of surprise, she seemed indifferent. Planning cautiously, I didn't ask her to go out, but I left determined to marry her. I thought and thought about a strategy to achieve my goal.

After I returned to my base, I tried to write to her. I crumpled up every letter. None of them seemed good enough. However, after many crumpled letters, I decided it was better to send an imperfect letter and give her the opportunity to make a decision about me than to wait until I could come up with a perfect letter that might be too late. I sealed my heart with the letter and mailed it. Days went by. Finally I received my answer that gave me hope.

As soon as I was given time off, I went to see Milly at the hospital where she stayed. We discussed our past experiences and our hopes and plans for the future. After a few months courtship I asked her to marry me. To my ecstatic joy, she agreed!

I braved the bombs of London as often as I could get leave to see her. I also saved all of my cigarettes to trade for chocolate, which I carefully wrapped and sent to her. It was a delight to please her.

During one of my visits Milly told me that Reverend Rose, her pastor, wanted to see me. With some anxiety, I made an appointment with the vicar. After I was seated in his office, I confidently answered his first question: “Edward, do you love Milly?”

“Yes sir, I do, with all of my heart.”

“I assume that Milly has told you that she might not be able to have children? How do you feel about that?” he asked.

“Well sir, I feel that my life has no meaning without Milly. Children would be nice, but it is she that I cannot live without.”

“And Edward,” he continued, “Milly is a Christian girl, and must not marry an unbeliever.”

“Reverend Rose, I know that I am not all that I should be, but I have certainly accepted Christ as my Savior, and I do desire to please Him and have Him work in my life.”

“That is all that can be asked. You’ll find, Edward, that the more you love the Lord Jesus, the more your earthly relationships will flourish. Milly is a loving, giving, wonderful girl. If you will love her as yourself she will give you a wonderful life.” He appeared satisfied with our interview, which pleased Milly immensely.

Later, we rode to town and chose her engagement ring. Her hand trembled as I placed it on her finger. Three diamonds on her ring represented three words, “I love you.”

Reverend Rose and members of his congregation gave us our wedding, and then surprised us with a beautiful honeymoon. However, no scenery, no honeymoon, or wonderful accommodations could compare with the delight of being married to Milly. She was all that I had dreamed of and more.

After our honeymoon Milly returned to the hospital, and I, to my air base. I took every opportunity to see her. She was a senior and was able to switch duty times with other nurses when I could get leave.

Sometimes we went to my parents’ home where they tried to give us privacy.

One evening, before my parents left for a night out, they suggested, “Pretend the house is yours. Cook what you wish for your supper.”

After they left, I sat down to read a book as Milly worked excitedly in the kitchen. When she was ready, she called me to the table where I was surprised with a beautiful plate of food served with the best china and silverware.

“Milly, these greens are delicious!” I praised her cooking, as I remembered the hated greens of my youth. “How did you make them so fresh-tasting?”

“My Mum taught me,” she said, and then looked a little sad. Milly’s mother had died five months before we were married.

“She would have been happy to see us now, wouldn’t she?” I added, also saddened that the lovely lady had not lived longer.

“I wish she could hear what I have to tell you.” Milly had a twinkle in her eye.

“What’s that, dear?”

“You’re going to be a father.”

“A what?”

“A father. I wasn’t sure about it, but now I am!” Milly’s eyes shone.

I jumped up and we danced around the room in each other’s arms.

We danced again on VE (Victory in Europe) Day and rejoiced also when the war in the Pacific was over (VJ Day). With no more air raids, weeks went by at the base without official orders.

Having completed seven years in the Air Force I was anxious to get back to civilian life to earn more money for my wife and expected child.

On September 3, 1945, I was called from a plane to the main office. ”You’re a father, Ware! You may take three days off!”

I had just sold my motorcycle and bought an old Singer car. It was a wreck. The steering wheel wiggled so much that I almost had to come to a full stop to keep it from wobbling. Somehow I managed to drive to the hospital where I found Milly radiant in bed. I ran to her. I felt overwhelmed with love for her. After a few moments I realized she had something to share with me. I looked into her blue eyes and then to where she pointed. It was a bassinet in the corner of the room.

“Our baby!”

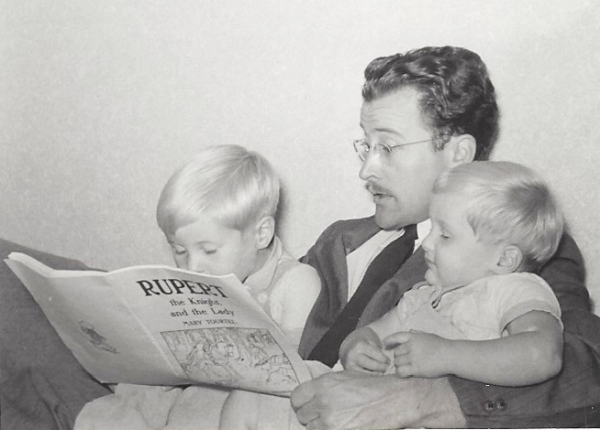

“Yes, our baby Kevin.” It was the name we had agreed upon. I walked over to meet my firstborn son.

A few months later the flight school closed, and we were all demobilized from military service. I drove to Cambridge where the government had a big deployment center. I exchanged my uniforms and equipment for a new civilian suit, shirt and tie. My severance pay wasn't much, but it was enough to give us a little money to begin our lives together.

I drove back to where Milly was living with her sister Ruth, and from there we began our civilian lives.

To earn money, I started another dance band while I was seeking a new job. Milly was not enthusiastic about the band but agreed with my motives. She always went with me to the dances, but didn't dance. Instead she sat on the sidelines and enjoyed talking with others who were watching the dancers. Milly became pregnant again, and as the baby developed, she felt uncomfortable at the dances.

“Would you mind if I stayed home?” she asked me one night.

“No darling, of course not. I’ll move the evening along quickly and rush home.”

One night at the dance a young girl made all sorts of unwanted suggestions, “You sure are a handsome fellow. Would you like to come home with me?”

“Excuse me, Miss, but I’m married.” I told her and thought that would end the matter. When we closed that night, to my horror, she was waiting for me outside.

She grabbed my arm, “Come with me. We can have a good time together.”

I broke away from her and ran home. When I entered the house, I threw my trumpet onto the bed and said, “I’ve had enough. I don't want any more of that!” So ended my dance band career.

A few days later in Coulsdon, I saw an unusual van drive up to a garage. The side windows of the van showed many tools inside. Intrigued, I realized I was looking at a traveling tool store. I told the driver that I would be interested in a job.

“I have worked with tools, all kinds of tools, all of my life, and I’ve also been a salesman.”

He was interested in me and took my address. A few days later I was invited for an interview with the company’s manager, and I got the job!

Full of enthusiasm and determination to do well, I drove the van to garages, machine shops and engineering works. Because there was such a shortage of tools after the war I found people eager to buy. I sold by commission and soon earned an excellent salary.

As time passed I sensed that the owners were unhappy with their decision to pay me a commission. I was now bringing home more than they thought a salesman should make.

At that time, October 26, 1946, our second son, Clive, arrived. We were a happy, blessed family.

One day as we took a ride in a new vehicle that I had just purchased, out of the blue, I asked Milly, “Would you consider moving to Canada with me?”

I could tell that she was surprised, but she did not miss a beat. She responded, “Ted, like Ruth in the Bible, I say, ‘Where you go, I will go.’ You’ve been to Canada and know what it is like. If you think it is a good idea for us to move there, I will back you up.”

Joy surged through me. “You’re a wonderful wife, Milly. I’m so grateful that you married me!”