Eddie (Ted)

Joins the Royal Air Force, 1938-1940

My first assignment in the Royal Air Force was boot camp. Six weeks of shooting, marching, and saluting. The second assignment was technical school where I became an airplane mechanic and fitter. At the end of the course each man was given an assignment to fabricate objects entirely by hand. We were required to fit complicated shapes like a puzzle to a thousandth of an inch.

The day after the final exam I entered the lunchroom and overheard two instructors in a heated conversation, “He’s better than you are!”

“Oh no he isn’t! Ware’s good, but I’m his teacher, and I’m best!”

“His is better than yours, and that’s all I can say,” the first one stated flatly. I decided it was best to leave quickly.

Back at the dorm I met with one of my new friends, Brian With. He was a Christian, and we often attended church services together. However, new movies were consistently shown on Sundays during chapel times. Sometimes I chose entertainment instead of the religious meeting. On the other hand, Brian never missed a chapel service, and he also prayed on his knees by his bed in the barracks morning and night. Sometimes men threw their boots at him, and they all heckled and ridiculed him unmercifully.

“With, why do you put up with it? You could pray in your bunk, and they’d leave you alone!” I suggested.

With was quiet for a few seconds, then quoted from the song,

Then he added, “Jesus went to the cross for me, this is the least I can do for Him.” As I still looked concerned he patted me on the back, “Don’t worry about me, Ware. I’ve got tough skin.”

Often men joked, “Where’s Ware?”

”He’s with With,” and they laughed.

On the same day I overheard my instructor speak about me, I reached the barracks at the same time as With, who had just come off of duty. “In the lunch room they were discussing who’s the best mechanic,” I told him as I hung up my jacket.

“And everyone said that it was you, right?” He looked at me with a grin.

“No, not everyone. The instructor angrily protested that of course since he was my teacher he was better. I’m concerned about where this might lead.”

“Sort of like King Saul and David in the Bible. Saul got upset that everyone in Israel thought more of David, a mere shepherd, than he, the king.”

With used his Bible to describe most events. Quoting from the Bible was difficult for most of the people around us to understand, but I enjoyed it.

“I guess you’re right. I think I’ll have to stay out of his path as much as possible.”

From that day on, the instructor was unreasonable. He graded me severely and caused me to miss the elite mechanic group status. I was very upset.

“It just isn’t fair, With!” I complained bitterly to my friend.

“All things work together for good, Ware. God may be working something out that you know nothing about.”

“Yeah,” I muttered, “maybe you’re right, but I still feel cheated.”

After the schooling, we were given orders and sent to bases around the country.

“With, I’m going to miss you. You have my respect and admiration, and I hope all goes well with you.”

“Ware, I’ve appreciated your being my friend when others threw things at me; I won’t forget it.” He shook my hand heartily.

I was sent to a squadron that had been in the Air Force for years. “Well, look what we’ve got here!” A tough old airman harassed me as we headed to the airplanes we were to service. “A mere baby! Did your Mum untie your apron strings yet?”

“Did Mumsy send you off with a clean hankie?” another man chimed in.

“I hope you don’t expect us to wipe your nose for you. This squadron is known for how tough we are, and we don’t take kindly to being sent infants that need diapering,” another sneered.

I ignored their jabs. I’ll show them what I can do, I thought. But no matter how hard I worked, it only seemed to annoy them.

A year after I joined the Air Force, war was declared and our squadron was told: “Pack up and put into storage all of your personal things. You are being sent to France.”

We were issued rifles and fifty rounds of ammunition. Very concerned about the order, I wondered if we were being sent to the front lines to be foot soldiers.

“Goin’ to cry, Ware?” one of the men teased. “Maybe you should go home to Mummy!”

I turned away from my tormentor. With such mates, who needed enemies?

We arrived in France by ship and were driven to Épernay in the north, then were ordered to clear land and set up an airfield to receive and service airplanes. Since we expected any minute to have to fight the Germans, the entire squadron worked hard and had the job done quickly. Warfare was stalled for nine months, however, as Germany held the Siegfried Line and France the Maginot.

After the airfield was set up, our days began at 6:30AM; I was assigned to play the wake-up call on my trumpet. Following wake-up, we went to the mess hall for breakfast.

“Little boy blue played his horn well this morning, didn’t he?” one of the squadron said as I passed his table.

“I don’t know which I hate worse, his lousy playing, or waking up,” his mate added.

After breakfast we exercised, practiced our duties, and ever alert for the sound of aircraft, rotated guard duty.

One warm morning I sat alone in the guard shack. The breeze brought in a bee that buzzed around the room but not locating nectar flew out again. War seemed far away as my eyes took in the vineyards as far as my eyes could see that surrounded the airfield. I glanced toward the roof of a farm cottage where I had been invited to share last night’s supper. A cute mademoiselle also was there. Neither of us had understood the other’s native language, but sparks had flown between us anyway.

I was distracted by a buzzing sound, an airplane. Jolted into the present, I remembered that I was to meet the aircraft as it landed. Since the closest route to the airfield was over the roof of the guard shack, I climbed up the wall and stepped gingerly onto the shingles. The brittle roofing disintegrated and I crashed through to the floor. Pain shot through my foot.

“The baby’s done got himself hurt,” were the words of comfort I received from those that found me. The Officer in charge sent me in a truck to the closest field hospital where they diagnosed my broken foot. The bottom half of my leg was then bandaged in a cast.

With my leg propped up, I sat on a cot and read or visited with the other patients.

One morning a new doctor made the rounds with the nursing staff. Each of us was required, if able, to stand at attention at the foot of his cot. As I stood, assisted by a crutch, I watched the doctor approach. He wore jackboots and jaspers, not exactly part of a British uniform.

“What’s the matter with you?” he looked me up and down. A nurse behind him read my diagnosis from her chart; then he snapped, “Can you walk?”

“Well, yes. It hurts, but I can walk,” I said.

“Lie down,” he ordered and yanked the leg cast off. I wondered whose side in the war he was on.

“Get up!” he demanded. The cast lay in bits at the foot of the bed. “Walk!”

I began to take small, painful steps. Within a few days I was fine. He knew what he was doing.

Before being sent back to my squadron I went to see the Officer in charge.

“Sir, please send me to a different squadron.”

“Why do you want to change Squadrons, Airman?”

“I’m not happy there, Sir. I could do a better job with a different group of men.”

“An unusual request. I’ll send you to another, but I’d better not hear any complaints about you. Try to make the best of every situation, Airman.”

“Yes, sir. Thank you, sir!”

My new squadron leader was an Australian named Jim Lease. He was jolly and always seemed to have his soldiers’ interests at heart. Under his leadership some of us were sent to the South of France where we practiced aerial bomb drops on rowboats in the Mediterranean. We also flew over temporary camps for thousands of refugees from the Spanish Revolution. We waved at them, and they were friendly as they waved back to us.

Sometimes we slept in beautiful French mansions with tall windows. The rooms, stripped of furniture, carpets and paintings, caused our boots and voices to echo throughout the big rooms. Most of the time, though, we stayed in rough farm huts with crude outhouses and straw-strewn dirt floors.

One day my squadron returned from the airfield to the village. “What in the world is that stench?” a soldier asked.

The indescribably awful odor hung over the whole area. “What a filthy, vile smell!” he continued. I agreed as we trudged together to the mess hall.

We lined up and were handed plates of Limberger cheese. Instantly we knew where the foul odor came from.

“What is this smelly stuff?” someone asked. We were aghast to think that we were expected to eat it. As hungry as we were, we could hardly bear the odor. After I cut the hunk of cheese, I noticed the odor lingered on my knife. Even when I buried the knife, and later resurrected it, the odor remained!

During our off hours we visited French bistros, drank wine, and enjoyed greeting the French mademoiselles. Also during our recreation times, we British soldiers sang and whistled ribald songs. Thomas, an especially gifted singer, was always called to “give us a song!” His father was one of the best comedians of London whom I had heard sing and perform pantomimes before the war.

Some men visited the red-light districts and encouraged me to join them, “Come on, Ware! You don’t know what you’re missing!”

I might not, but I do know I’m not getting diseases that are in those places, I told myself.

When the men were headed in that direction I looked for other things to do. Sometimes I remembered With and felt guilty about not going to chapel services. It was rare to find a good chaplain. Most of them served solely as social workers.

One day at mess hall, I looked up to see Goff, an old friend from the Coulsdon Sunday afternoon Bible Class.

“Goff! A vision from home! Come sit here!” We recounted what had happened to us through the last year, where we’d gone and what we’d done. Then Goff asked, “What’s the Chaplain like here?”

“Well, I can’t say as I know, but we can find out.”

We attended a service together and found the chaplain to be quite good. He warned us, “In every person there are two fires, a wild fire that gets fueled by worldly, evil things, which can engulf and destroy; and the hearth of our heart. If we read the Bible and pray, our hearts get warm and soft enough to help those around us. It all comes down to which fire gets fueled.”

I realized that I needed to extinguish some wild fires in my life and prayed, “Oh God, it’s not easy to be a Christian. I do love you, and ask for you to keep me and help me.”

June of 1939 saw the German forces march around the Maginot and Siegfried lines. They invaded Belgium and then France. Suddenly we did not have enough hours in the day. Every airplane had a logbook, and we had certain planes that each of us was responsible to service. Many aircraft that we sent off never returned; some came back in with engines dangling off of the wing or propellers missing.

When our airplanes were parked on the airfield we mechanics had to stay beside them, ready to spring into action and start the engine when the alarm sounded. The pilots in their quarters heard the same alarm and immediately dressed, put on parachutes and ran to their aircraft. By the time they reached us the plane was ready to fly. They jumped into their cockpit, while we helped strap them in.

“Good luck,” we murmured, “come back soon.”

British troops coined a phrase, “Joe for King!” which represented the common soldier’s frustration with war.

Our monarch, King George, represented all that we were fighting for in the war. To speak irreverently of him in this time of national crisis was severely frowned upon.

“Joe” was the name of the ruthless murderer dictator of the Soviet Union, Joseph Stalin, who starved millions of peasants who opposed him. To refer to this inhumane dictator as our king, even in jest, was risking severe punishment.

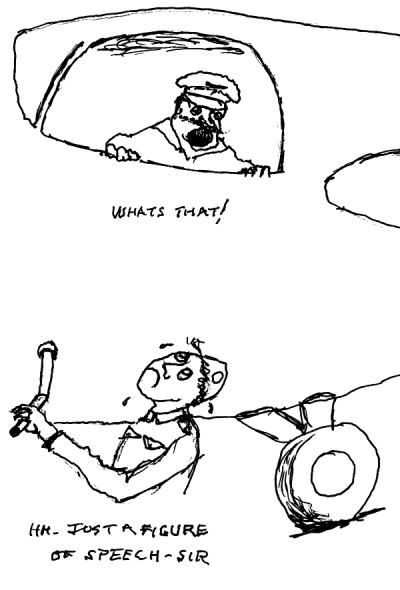

It was not in jest, however, but in extreme frustration, that I uttered the unspeakable words and risked my Air Force career. I was trying to start a twin engine plane. The pilot was already in the cockpit with the window open waiting for me. I had turned the crank so many times that I was breathless. Exhausted, I panted, “Oh, Joe for King!”

JUST A FIGURE OF SPEECH

The pilot stuck his head out of the window and said, "What was that?"

My heart froze within me. I had just said something that could put me in the brig.

“Just a figure of speech, sir,” I said weakly and cranked with all of my might. I thought I heard him laugh. As he took off he waved, which I hoped meant that he did not hold my outburst against me.

Of the original group of mechanics that I trained with, I learned that none of them returned home alive. When I heard this, I considered my friend With’s words: “All things work together for good; God may be working something out that you know nothing about.” I grieved over the loss of my companions’ lives, and wondered why God had saved mine.

We also lost our much-loved Officer, Lease, who died in a plane wreck. Another valuable life snuffed out. As the war got hotter we witnessed line after line of weary and injured soldiers returning from the front lines. If there is any glory in war it was not seen in the defeated, miserable faces that we saw pass through our airfield each day.

One morning I woke up feeling nauseous. My stomach hurt, and when I stood, it hurt much worse. I dragged myself to the infirmary where a nurse took my temperature and helped me to a chair. A doctor checked me.

“Appendicitis,” was his diagnosis.

I was put onto a truck and driven to a field hospital in another town where I waited all day for attention. The doctors were extremely busy with the injured coming in from the front lines. In the evening a doctor came through the ward and stopped in front of me, glanced down at the chart, then back at me. “What's that doing there?” he asked of the little kidney basin that sat by my bedside.

The nurse responded, “He felt sick, sir. It’s there in case he vomits.”

“Get him to the operating room immediately. His appendix may have burst.”

The nurses moved quickly, and the next thing I remember is pain. I moaned and was surprised that a nurse came immediately over to see me. She said brightly, “Hello soldier. I see you’ve decided to wake up.” She pulled the sheet down from my waist and to my horror I saw a big pipe sticking out of my stomach.

“What’s that!” I quailed.

“Nothing to worry about. Your appendix ruptured and this is the drain.” Then she rushed off.

“What’s her hurry?” I asked the man next to me.

“I think there are more patients than she has time for. I just came from the front and the casualties are enormous. All British troops are in retreat.”

I was in the hospital for a few days, then all patients were transferred to trucks taking us to boats headed for England. I found myself next to men with stumps for legs and arms. Some had bandages across their heads and faces. I lay quietly and thought deeply about life and death and war. How easily our candle can be snuffed out. I learned later that my squadron had been ordered to bomb the river Meuse to halt the advance of the German invasion. Every one of our planes was wiped out with all of our support crews literally running for their lives. Sadly, some very dear friends of mine were killed, including Thomas, the man with the golden voice.

In England I was sent to a hospital to recuperate. One of the nurses, Nelly, became quite fond of me. We went for walks and talked.

“Nelly, when I was a child I was taught that people went to hospitals to die, and that all nurses were wicked.”

“So what do you think now?”

“The opposite. Nurses are giving, dedicated people.”

“Thank you,” she smiled.

“Edward, I wonder where you’ll be sent when you get better?”

“I don’t know. Not back to France. Everyone who was still alive came back at Dunkirk,” I said.

“My father sent our family’s row boat on that rescue,” she said. “I thought that it was stupid, as the channel is a rough piece of water to cross, and I was sure our little boat would sink. But it didn’t. It rescued five men!”

“I believe God did a miracle. Fog covered the operation so the Germans couldn’t see what was going on, and the water was totally smooth so the men were able to be rescued from the beaches.”

We walked on in silence as we contemplated the wonder of it. I enjoyed Nelly’s friendship, but was intimidated by her being an officer. She would have been reprimanded if caught socializing with me, an airman.

A few weeks later I was sent home where it was a delight to relax and be catered to by my mother. My father continued at his job in London, my sister Joan worked at the American Embassy as a telephone operator and my brother Cliff was in the Navy on a carrier.

After I recovered fully, I received orders to report to the Night Fighters, a squadron whose planes went on night missions. Radar, called IFF (Identification, Friend or Foe) was new at this time. It was so secretive that none of us really knew what it was all about. Curiously, an extra seat was installed in the cockpit for an Observer who gazed into a little tube to identify aircraft. At the same time we were issued carrots to eat, as many carrots as we could consume. The pilots continually munched on carrots. The idea was to mislead “Jerry” to conclude our extraordinary eyesight came from the vitamin A in carrots! Of course, the deception was soon discovered and the enemy learned that we were using radar.

For a diversion from the sadness of war, I pulled together a few friends to make a bit of money on the side. We formed a band and played for dances on Sunday evenings. We often went to pubs and enjoyed our camaraderie away from the dull barracks. Officers set rank aside and also joined us there, as well as American service men.

The American troops ate better food, had nicer uniforms, and made more money than we did. We resented it, especially when our English girls favored them. But the Americans had their own problems. When they got drunk they often exhibited their racial prejudices, which resulted in nasty fights and brawls.

Shortly after, Germany started a heavy Luftwaffe air raid on England, beginning the Battle of Britain. Women and children were evacuated from London and other large cities, and blackouts were enforced. London was the prime target. Fifty bombers escorted by more than a hundred fighters smashed the capital.

Our squadron also was often bombed. Many of our men were killed, war planes destroyed, and the hangars blown to smithereens. It was a horrific time. Our nerves were stretched to the limit as we stayed up night after night attending airplanes. Often struck with terror, I stood at my post of duty and watched the enemy’s planes come in. I wondered, “Is this going to be it? Is this the end?” I dived to the ground and covered my ears with my hands as the whine of bomb after bomb screeched its way to earth. The bombs pulverized whatever they hit. Anyone within forty to fifty feet of a bomb’s detonation was killed or maimed by the shrapnel. Sometimes I felt the powerful blast of wind that accompanied a close hit. The roar of anti-aircraft guns and screams of the injured created a living hell that I longed to escape.